Stadtluft macht frei.

Terry Pratchett (2002). Night Watch. HarperCollins. p 334

2.

City Planet

Against the dark screen of night, Vimes had a vision of Ankh-Morpork. It wasn’t a city, it was a process, a weight on the world that distorted the land for hundreds of miles around. People who’d never see it in their whole life nevertheless spent that life working for it. Thousands and thousands of green acres were part of it, forests were part of it. It drew in and consumed…

…and gave back the dung from its pens, and the soot from its chimneys, and steel, and saucepans, and all the tools by which its food was made. And also clothes, and fashions, and ideas, and interesting vices, songs, and knowledge, and something which, if looked at in the right light, was called civilization. That was what civilization meant. It meant the city.

—Terry Pratchett, Night Watch

Cities are wealth creators; they always have been. They are population sinks, and always have been. Just as agriculture raised the world’s carrying capacity for humans, so did cities. The death rate from “constant battles” declined with urbanization, LeBlanc says, because “as the city folk make tools and improve the technologies that make the farming more efficient, more people can live in the city instead of farming, and the cities grow. To some degree, this process solves the resource/population pressure found among farmers.”

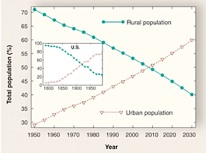

The ten-thousand-year flow of people to cities has become a torrent. In 1800 the world was 3 percent urban; in 1900, 14 percent urban; in 2007, 50 percent urban. The world’s population crossed that threshold—from a rural majority to an urban majority—at a sprint. We are now a city planet, and the Greener for it, as I’ll show.…

“In the village, all there is for a woman is to obey her husband and relatives, pound millet, and sing. If she moves to town, she can get a job, start a business, and get education for her children.” That remark at a conference in 2001 exploded my Gandhiesque romanticism about villages. The speaker was Kavita Ramdas, head of the Global Fund for Women.…

The move to town is a liberation. A New York Times story in 2005 related that

Gandhi idealized villages as the way to return Indians to their precolonial state. B. R. Ambedkar, the Dalit, or untouchable, leader who helped write India’s Constitution, saw it differently: he called villages a cesspool, “a den of ignorance, narrow-mindedness and communalism,” and urged untouchables to flee them for urban anonymity.…

Lou Reed sings, “When you’re growing up in a small town/ You know you’ll grow down in a small town./ There’s only one good use for a small town:/ You hate it, and you know you’ll have to leave.” In America’s northern high plains, cities like Fargo, Bismarck, and Grand Forks are thriving, but the rest of the vast grasslands is emptying, leaving ghost towns and decaying farmhouses. National Geographic describes “a sense of things ebbing, of churches being abandoned, schools shutting down, towns becoming ruins.” Some megafauna—moose and mountain lions—are coming back. The whole high-plains region from eastern Montana to northern Texas is headed toward becoming the “buffalo commons” that environmentalists long for.

In developed countries like the United States, the migration is from boring, lonely, and hard to exciting, busy, and pleasant—toward coasts, sun, and densely citified regions called “megapolitan areas,” such as the one encompassing everything on the eastern seaboard from Boston to Richmond, Virginia.…

Fifty years later, in 1950, the leading ten cities had doubled in size, and Shanghai, Buenos Aires, and Calcutta had joined the list. Fifty years after that, in 2003, the top ten cities had further tripled in size, but that was the least of their changes.…

The “rise of the West” is over. The world looks the way it did a thousand years ago, when the ten largest cities were Córdoba, in Spain; Kaifeng, in China; Constantinople; Angkor, in Cambodia; Kyoto; Cairo; Baghdad; Nishapur, in Iran; Al-Hasa, in Saudi Arabia; and Patan, in India. As Swedish statistician Hans Rosling says, “The world will be normal again; it will be an Asian world, as it always was except for these last thousand years. They are working like hell to make that happen, whereas we are consuming like hell.…”

Marxist scholar Mike Davis gives perspective on the phenomenon in his 2006 book, Planet of Slums:

In Africa … the supernova-like growth of a few giant cities like Lagos (from 300,000 in 1950 to 10 million today) has been matched by the transformation of several dozen small towns and oases like Ouagadougou, Nouakchott, Douala, Antananarivo and Bamako into cities larger than San Francisco or Manchester.…

The oldest surviving corporations, Stora Enso in Sweden and the Sumitomo Group in Japan, are about 700 and 400 years old, respectively. The oldest universities, in Bologna and Paris, have lasted only 1,000 years so far. The oldest living mainstream religions, Hinduism and Judaism, date back about 3,500 years. But the town of Jericho has been continuously occupied for 10,500 years. Its neighbor Jerusalem has been an important city for 5,000 years, even though it was conquered or destroyed thirty-six times and endured eleven conversions from one religion to another. Many cities die or decline to irrelevance, but some thrive for millennia.

I suspect that one cause of their durability is that cities are the most constantly changing of organizations. In Europe they consume 2 to 3 percent per year of their material fabric (buildings, roads, and other construction) through demolition and rebuilding.…

“Cities make countries rich. Countries that are highly urbanized have higher incomes, more stable economies, stronger institutions. They are better able to withstand the volatility of the global economy than those with less urbanized populations.” So notes the United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-HABITAT), which was impelled to its city-boosting position by revelations in the worldwide data it has been gathering since 1978.

The reversal of opinion about fast-growing cities—from bad news to good news—began with The Challenge of Slums, a 2003 UN-HABITAT report. The book’s reluctant optimism came from its groundbreaking fieldwork—thirty-seven case studies in slums worldwide. Instead of just compiling numbers and filtering them through remotely conceived theories, the researchers hung out in the slums, talking to people. They came back with an unexpected observation: “Cities are so much more successful in promoting new forms of income generation, and it is so much cheaper to provide services in urban areas, that some experts have actually suggested that the only realistic poverty reduction strategy is to get as many people as possible to move to the city.”

In 2007 the United Nations Population Fund gave that year’s report the upbeat title Unleashing the Potential of Urban Growth. The lead author, Canadian demographer George Martine, wrote, “Cities concentrate poverty, but they also represent the best hope of escaping it.” He declared in a talk that “80 to 90 percent of GNP growth occurs in cities” and that “the half of the world’s population living in cities occupies only 2.8 percent of the world’s land area.…”

“The world’s 40 largest mega-regions, which are home to some 18 percent of the world’s population,” writes urban theorist Richard Florida, “produce two-thirds of global economic output and nearly 9 in 10 new patented innovations.…”

_________

A new theory is upsetting our idea of what cities are and can become. Through a phenomenon known as Kleiber’s law, organisms become more metabolically efficient as they scale up—from shrew to elephant, say. Cities do the same.…

Individual productivity rises (15% per person when the city doubles) as people get busier. Average walking speeds increase. Businesses, public spaces, nightclubs, and public squares consume more electricity.…

If cities are concentrators of efficiency and innovation, an article about the scaling paper in Conservation magazine surmised, then, “the secret to creating a more environmentally sustainable society is making our cities bigger. We need more metropolises.” (I am a contributing editor for Conservation.)

In Peter Ackroyd’s London: The Biography (2000), he quotes William Blake—“Without Contraries is no progression”—and ventures that Blake came to that view from his immersion in London. “Wherever you go in the city,” Ackroyd observes, “you are continually being assaulted by difference, and it could be surmised that the city is simply made up of contrasts; it is the sum of its differences.…”

The common theory of the origin of cities states that they resulted from the invention of agriculture: Surplus food freed people to become specialists. You can’t have full-time cobblers, blacksmiths, and bureaucrats, the theory goes, without farms to feed them. Jane Jacobs upended that supposition in The Economy of Cities (1969). “Rural economies, including agricultural work,” she wrote, “are directly built upon city economies and city work.…”

Agriculture, it appears, was an early invention by the dwellers of walled towns to allow their settlements to keep growing, as in Geoffrey West’s formulation. Today’s megacities rely on the same flow of innovation. A 2006 UN-HABITAT report proposed that

Cities are engines of rural development.… Improved infrastructure between rural areas and cities increases rural productivity and enhances rural residents’ access to education, health care, markets, credit, information and other services.…

A study in Panama showed what happened when people abandoned slash-and-burn agriculture to move to town: “With people gone, secondary forest has regenerated. Crucially, if protected from hunters, nearly every bird and mammal species found in primary forest has also been found in secondary.” Fifty-five times more tropical rain forest is growing back each year than is being cut, according to a 2005 report on world forests from the UN: 38 million acres of primary forest is cut, but 2.1 billion acres of secondary forest is growing back on land that was once farmed, logged, or burned.…

But the squatter cities are vibrant. Their narrow lanes are bustling markets, with food stalls, bars, cafés, hair salons, dentists, churches, schools, health clubs, and mini-shops trading in cellphones, tools, trinkets, clothes, electronic gadgets, and bootleg videos and music.…

Why would anyone leave a brick house in the village with its two mango trees and its view of small hills in the East to come here?…

By 2004 I knew something important was up with the rampant urbanization of the developing world, but I couldn’t find much in the way of ground truth about it until the publication of Shadow Cities: A Billion Squatters, a New Urban World, by journalist Robert Neuwirth.…

Though the squatters join forces for what the UN researchers describe as “cultural movements and levels of solidarity unknown in leafy suburbs,” they are seldom politically active beyond defending their own community interests.

A depiction of contemporary slum reality even more vivid than Neuwirth’s is an autobiographical novel by an escaped Australian prisoner who went into hiding in Mumbai’s slums, joined its organized crime world, and fell in love with the city. The author of Shantaram (2005), Gregory David Roberts, writes with all of the intensity and journalistic detail of a Victor Hugo, but from a level of experience that Hugo never had.…

Social cohesiveness is the crucial factor differentiating “slums of hope” from “slums of despair.” This is where CBOs (community-based organizations) and the NGOs (national and global nongovernmental organizations) shine. Typical CBOs include, according to UN-HABITAT’s The Challenge of Slums (2003), “community theatre and leisure groups; sports groups; residents associations or societies; savings and credit groups; child care groups; minority support groups; clubs; advocacy groups; and more. … CBOs as interest associations have filled an institutional vacuum, providing basic services such as communal kitchens, milk for children, income-earning schemes and cooperatives.”

Robert Kaplan reported in 2007 that the NGOs in Bangladesh “represent a whole new organizational life-form.” In the cities and villages, they “make an end run around dysfunctional governments,” and “because Bangladeshi NGOs are supported by international donors, they have been indoctrinated with international norms to an extent unmatched by the private sector.”

_________

Women play a pivotal role in all this. The UN report notes that CBOs “are frequently run and controlled by impoverished women and are usually based on self-help principles, though they may receive assistance from NGOs, churches and political parties.” A major impact of the move from countryside to city is that it unleashes woman power. Lenders have learned that microfinance credit works best when provided to women instead of men; and women are the more responsible holders of property deeds. The Challenge of Slums summarizes: “In many cases, women are taking the lead in devising survival strategies that are, effectively, the governance structures of the developing world when formal structures have failed them. However, one out of every four countries in the developing world has a constitution or national laws that contain impediments to women owning land and taking mortgages in their own names.”

It is so important to free up newly urbanized women from their traditional role as fetchers of water and fuel that, as the UN report drily suggests, “the provision of water standpipes may be far more effective in enabling women to undertake income-earning activities than the provision of skills training.”

A 2007 UN report, Growing Up Urban, tells the story of Shimu, a woman in her early twenties who moved from a small village in northern Bangladesh to a garment-making job in Dhaka:

For the first time in her life she had got rid of her husband, her in-laws, her village and their burdens. A few months after she arrived, Shimu, now able to support her children, mustered the courage to return to her town and file for divorce. …

Shimu prefers living in Dhaka because “it is safer, and here I can earn a living, live and think my own way,” she says. In her village none of this would have been possible. But she thinks that when she is older she will go back there. She plans to buy a piece of land and settle there.

That bond back to the village appears to be universal. The Challenge of Slums observes that “Kenyan urban folk who have lived in downtown Nairobi all of their lives, if asked where they come from, will say from Nyeri or Kiambu or Eldoret, even if they have never been to these places. They will be taken there to be buried on ancestral land when they die.” The persistence of that soul-bond to the land could be a great asset for assuring eventual environmental recovery in the developing countries, when love of the land plays out as protection of the land.

Religious groups have a stronger support role in the slums than most people realize. As Mike Davis wrote in New Left Review,

Populist Islam and Pentecostal Christianity (and in Bombay, the cult of Shivaji) occupy a social space analogous to that of early-twentieth-century socialism and anarchism.…

In the 2007 UN report, George Martine noted that “Rapid urbanization was expected to mean the triumph of rationality, secular values and the demystification of the world.…”

Praise be to plastic pipe. All honor the prefab window. Bow down to sheets of old plywood, stock-model sinks, mass-produced tile.…

The magic ingredient of squatter cities is that they are improved steadily and gradually, increment by increment, by the people living there. Each home is built that way, and so is the whole community. To a planner’s eye, squatter cities look chaotic. To my biologist’s eye, they look organic.

Prince Charles has the same opinion. After visiting Mumbai’s Dharavi slum, he told an audience in London, “I find an underlying, intuitive grammar of design that subconsciously produces [a place] that is walkable, mixed-use, and adapted to local climate and materials—which is totally absent from the faceless slab blocks that are still being built around the world to warehouse the poor.”

According to urban researchers, squatters are now the predominant builders of cities in the world.

_________

Inside the homes of the older squatter communities is another surprise. Field researchers in Thailand for the 2003 UN report found that

All slum households in Bangkok have a colour television. The average number of TVs per household is 1.6. … Almost all of them have a refrigerator. Two-thirds of the households have a CD player, a washing machine, and 1.5 cellphones. Half of them have a home telephone, a video player and a motorcycle.

Back in 1970, Janice Perlman interviewed 750 residents in the favelas of Rio. Her resulting book, The Myth of Marginality (1976), observed that the favelados “have the aspirations of the bourgeoisie, the perseverance of pioneers, and the values of patriots.” Thirty years later, in 2001, she went back to interview her original informants and their children.…

A reporter from the Economist who visited Mumbai wrote that “Dharavi, which is allegedly Asia’s biggest slum, is vibrantly and triumphantly alive. … In fluorescent-strip-lit shops, in snatched exchanges in the pedestrian crush, as a hookah is passed around a tea-stall, again and again, the stories are the same. Everyone is working hard and everyone is moving up.…”

The Challenge of Slums—the 2003 United Nations report—that 60 percent of urban employment in the developing world is in the informal sector and that the informal economy has essential links to the success of the formal sector:

The screen-printer who provides laundry bags to hotels, the charcoal burner who wheels his cycle up to the copper smelter and delivers sacks of charcoal… , the home-based crèche to which the managing director delivers her child each morning, the informal builder who adds a security wall around the home of the government minister, all indicate the complex networks of linkages between informal and formal.

In many cities, the roughest slums are pressed right up against the most affluent neighborhoods. It looks like grotesque inequity, and it is, but it’s mainly an efficient economic event typical of city density—service supply and service demand cleaving close to one another.…

At the entry level, the informal economy is organized around pittances. Robert Kaplan wrote in 2008 that

For the many rural newcomers to Bangladesh’s cities, there is the rickshaw economy, as much an animating force in urban areas as the search for usable soil is in villages.…

The slums of the world teem with invisible private schools of just a few teachers selling their services directly for pennies. As Clive Crook reported in the Atlantic, “The parents of full-fee students, desperately poor themselves, willingly subsidized those in direst need. On the whole, dime-a-day for-profit schools are doing a better job of teaching the poorest children than the far more expensive state schools.”

This book was finished before the full effects of the world financial crisis of 2009 could be studied. Did the informal economy in the world’s slums offer a refuge from it, or did people there suffer more than anybody? (A 2009 report in the Wall Street Journal said that in the developing world, “people are landing in the informal sector, which has become a critical safety net as the economic crisis spreads.…”) Were some people driven further into the crime economy? For that matter, how did global crime do? Did the rate of urbanization slow down or speed up? Here’s my prediction from March 2009: significant growth in the informal economy from more people retreating into it; significant growth in the crime economy, because it’s always ready to exploit chaos; no change in the rate of urbanization. How wrong was I?

AES, among many other corporations, was inspired by C. K. Prahalad’s The Fortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid: Eradicating Poverty Through Profits (2005). The book spells out how companies can reach the world’s 4 billion poor and deliver goods and services at the interface between the formal and informal economies. Prahalad writes that the poor shop after seven p.m.; they buy in tiny quantities; they welcome relief from the premium prices they often have to pay to slum (sometimes criminal) monopolies; and they are comfortable leapfrogging to new technologies.

Corporations are right to pay attention to what is now referred to as the BOP—bottom of the pyramid. A large portion of humanity on the loose, trying new things in new cities, is a lot of potential customers, collaborators, and competitors, and while the income of the poor is currently small, it is growing fast. And the aggregate numbers are formidable. A 2007 book, The Next Four Billion, declares:

The 4 billion people at the base of the economic pyramid—all those with incomes below $3,000 [per year] in local purchasing power—live in relative poverty.…

A sense of the immense scale and damage of the criminal market can be found in the book Illicit (2005) by Moisés Naím.…

William Langewiesche, writing in Vanity Fair, saw the PCC as part of a much larger phenomenon, which he called the “feral zone”:

That zone is a wilderness inhabited already by large populations worldwide, but officially denied and rarely described.…

One idea put forward early was Hernando de Soto’s. In his seminal 1989 book, The Other Path, he was the first to honor the way the informal economy works, based on research in the squatter communities of Lima. His theory was that squatters could break out of poverty if only they could get bankable title to their shacks. The idea has been tried, but it mostly doesn’t work in urban slums: The practice doesn’t help with credit, it encourages building owners to become absentee landlords, and it attracts rich raiders. Neuwirth wrote in Shadow Cities:

It doesn’t matter whether you give people title deeds or secure tenure, people simply need to know they won’t be evicted. When they know they are secure, they build.…

“The best plans generally let the slum dwellers themselves make the main decisions in planning their future. You should provide clean water, toilets, electricity, garbage collection and disposal, and maybe let people build their own houses if they can, using materials that you can provide,” says Aprodicio Laquian, the Filipino-Canadian planner who practically invented the idea of slum-dweller-designed urban rehabilitation in the 1960s. … These sorts of schemes, known as “slum upgrading” or “sites and services,” have been at the heart of the most successful urban-renewal projects of the past 40 years.…

As the 2003 UN report points out, “When more than half of the urban population lives in them, the slums become the dominant city.…”

“India Accelerating: The Great Migration

All Roads Lead to Cities, Transforming India,” Amy Waldman. New York Times, December 7, 2005

“The Emptied Prairie,” Charles Bowden, National Geographic (Jan. 2008), p. 146

Tertius Chandler (1987). 4,000 Years of Urban Growth. St. David’s Univ.

Steven LeBlanc, Katherine Register (2003). Constant Battles: Why We Fight. St. Martins. p 177.

At almost exactly the same time that the world became half urban it became half middle-class “thanks to rapid growth in emerging countries,” reported The Economist in Feb. 2009.

Mike Davis (2006). Planet of Slums. Verso. p 8

United Nations Human Settlements Programme (2006). The State of the World's Cities 2006/2007 Earthscan. p 5

“Scientist of the Year Notable: Hans Rosling,” Jennifer Barone. Discover, Dec. 6, 2007

So I was told by Francis Duffy, former president of the Royal Institute of British Architects.

The State of the World's Cities 2006/2007. p 46

UN Habitat (2003). The Challenge of Slums: Global Report on Human Settlements. Earthscan. p 27

State of World Population 2007: Unleashing the Potential of Urban Growth. United Nations Population Fund. p 1

“How the Crash Will Reshape America,” Richard Florida. Atlantic, March 2009

United Nations Human Settlements Programme (2004). The State of the World's Cities 2004/2005 Earthscan. p 160

“Growth, innovation, scaling, and the pace of life in cities,” Luís M. A. Bettencourt, José Lobo, Dirk Helbing, Christian Kühnert, and Geoffrey B. West. PNAS | April 24, 2007 | vol. 104 | no. 17 | 7301-7306

“Urban Myths,” Jonah Lehrer. Conservation, January-March, 2008.

“Cities: Large is Smart” Jenna Beck. SFI Bulletin, Spring, 2008.

Peter Ackroyd (2000). London: The Biography. Doubleday. p 753

Jane Jacobs (1969). The Economy of Cities. Vintage. p 4

Lewis Mumford (1956). “The Natural History of Urbanization” In Thomas, William L. Jr. (Ed.), Man’s Role in Changing the Face of the Earth. Univ. of Chicago. p 385

United Nations Human Settlements Programme (2006), The State of the World's Cities 2006/2007. Earthscan. p 47

“New Jungles Prompt a Debate on Rain Forests”, Elisabeth Rosenthal. New York Times, Jan. 29, 2009.

I should have made a bigger fuss in the book about this extraordinary good news on the regrowth of rainforests. Track the data down to the original sources, and here’s what you find.

“Dirty, Crowded, Rich and Wonderful”, Suketu Mehta. New York Times, July 16, 2007.

The Challenge of Slums, p 57

Robert Neuwirth (2004). Shadow Cities. Routledge.

“Not Everyone is Grateful as Investors Build Free Apartments in Mumbai Slums”, Anand Giridharas. New York Times, Dec. 15, 2006.

The Challenge of Slums, p 151

“Waterworld”, Robert D. Kaplan. Atlantic, Jan.-Feb., 2008.

The Challenge of Slums, p 151

The Challenge of Slums, p 60

Growing Up Urban: State of the World Population 2007 Youth Supplement. UNFPA. p 31

The Challenge of Slums, p 32

“Planet of Slums”, Mike Davis. New Left Review 26, Mar.-Apr., 2004. p 30

Unleashing the Potential of Urban Growth, p 26

Shadow Cities, p 55

“Globalization from the Bottom Up”—speech on Feb. 5, 2009

The Challenge of Slums, p xxx

The Challenge of Slums, p 104: “The poor are currently the largest producers of shelter and buillders of cities in the world.”

“Marginality from Myth to Reality: The Favelas of Rio de Janeiro 1968-2005,” Janice E. Perlman. Jan. 20, 2007.

“Urban Poverty in India.” Economist. Dec. 19, 2007.

The Challenge of Slums, pp 29 and 56

The quote is from a responder to Zuckerman’s blog—a Medellín resident named “medea.”

“Waterworld”, Robert D. Kaplan. Atlantic, Jan.-Feb., 2008.

“The Ten-Cent Solution”, Clive Crook. Atlantic, March, 2007.

“The Rise of the Underground”, Patrick Barta. Wall Street Journal, March 14, 2009.

The Next Four Billion:Market Size and Business Strategy at the Base of the Pyramid, World Resources Institute, 2007. p 3

“City of Fear,” William Langewiesche, Vanity Fair. April, 2007.

“Marginality from Myth to Reality: The Favelas of Rio de Janeiro 1968-2005,” Janice E. Perlman. Jan. 20, 2007.

Shadow Cities, p 302

“Slumming it is better than bulldozing it,” Doug Saunders. Globe and Mail, Jan. 12, 2008.

The Challenge of Slums. p 57

A fine account by Kevin Kelly on how great cities squat themselves into existence is here.

One of the few organizations exploring the realities of the informal economy is the MIT-based Poverty Action Lab.

WebUrbanist has a nice blog item on the 10 cities it deems the longest continuously inhabited: Damascus, Jericho, Susa, Plovdiv, Jerusalem, Tyre, Athens, Lisbon, Varanasi, Cholula.

The Challenge of Slums, p 149

“Panic Over for Threatened Rainforest Species?”, Adrian Barnett. New Scientist, May 9, 2007. Further quote concerning Puerto Rico: "When rural people moved to the cities, forest cover increased from 7 per cent to the current 45 per cent."

A formal version of this prediction appears online here, where it can be discussed and voted on.

There are signs that the violent rivalry in the favelas between drug gangs and the militias is starting to be won by the militias. That might be a path toward eventual stability. Details here.

Lewis Mumford wrote of medieval cities: “Organic planning does not begin with a preconceived goal; it moves from need to need, from opportunity to opportunity, in a series of adaptations that themselves become increasingly coherent and purposeful, so that they generate a complex final design, hardly less unified than a pre-formed geometric pattern." (Source)