Larry Brilliant says there is an important additional reason for dropping birthrates in the developing world.

Robert Frost (1947). A Masque of Mercy. Holt. p 5. The book is a short play.

John Brockman, editor (2007). What Are You Optimistic About? Harper. p 220

“Upwardly Mobile in Africa,” Jack Ewing. BusinessWeek , Sept 24, 2007

Nicholas Sullivan (2007). You Can Hear Me Now. Wiley. p 155

“Can the Cellphone Help End Global Poverty?,” Sara Corbett. New York Times Magazine, Apr. 13, 2008

“Revolution in Remittances,” Nicholas Sullivan. You Can Hear Me Now blog, March 20, 2007

Allen Hammond et al. (2007). The Next 4 Billion. Univ. California. p 104

“Smartphones are the PCs of the Developing World,” Jessica Marshall. New Scientist, Aug. 1, 2007

“Building Big, Starting Small,” Ethan Zuckerman. Boston Globe, Aug. 5, 2007

Nicholas Sullivan (2007). You Can Hear Me Now. Wiley. p 10

You Can Hear Me Now. p 146

“Planet’s Fastest Revolution Speaks to the Human Heart,” Joel Garreau. Washington Post, Feb. 24, 2008

“Sanctuaries of Disconnection,” Kevin Kelly blog, Jan. 19, 2008

David Damrosch (2007). The Buried Book. Holt. p 223

Paul Ehrlich(1968). The Population Bomb. Ballantine. p 130

The Swiss-American photographer Robert Frank made a 37-minute film of the event, titled “Liferaft Earth.” It can be found in some museum collections and on a DVD available here.

Wallace Kaufman (1994). No Turning Back. Basic. p 176

“The Global Baby Bust,” Phillip Longman. Foreign Affairs, May-June 2004.

Phillip Longman (2004). The Empty Cradle. Basic. p 8

Paul Polak (2008). Out of Poverty. Berrett-Koehler. p 172

Unleashing the Potential of Urban Growth. p 69

The Empty Cradle. p 63

“Demographic Trends that May Impact U.S. Interests and Global Stability over the Next 30 Years—

Workshop Preparation Document,” Monitor Group,

6 March 2008

“France Touts Rising Fertility Rate,” Pierre-Yves Roger. Washington Post, Jan. 16, 2007

“France Claims EU Fertility Crown,” Caroline Wyatt. BBC News, Jan. 16, 2007

The State of the World's Cities 2006/2007. Earthscan. p 120

“No Babies?” Russell Shorto. New York Times, June 29, 2008

Interview with Treasurer Peter Costello, Sep. 22, 2006

Ben Wattenberg (2004). Fewer. Ivan R. Dee. p 213

“Redefining Cities,” Peter Calthorpe. Whole Earth Review, March, 1985. p 1

“Towards Livable Cities,” Darryl D’Monte. The Hindu, Mar. 15, 2009.

“Redefining Cities,” Peter Calthorpe. Whole Earth Review, March, 1985. p 1

“Recycling in Asia’s Biggest Slum.” Economist, Dec. 19, 2007.

“Thronged, Creaky and Filthy.” Economist, May 3, 2007.

“The Promise of ‘Environmentals’ in Lagos, Nigeria,” John Boonstra. UN Dispatch, Jan. 7, 2009.

“Green Manhattan,” David Owen. New Yorker, Oct. 18, 2004.

The State of the World’s Cities 2006/2007. p 47

Mark London, Brian Kelly (2007). The Last Forest. Random. p 244

This particular list comes from the Grist blog item “15 Green Cities,” July 19, 2007

“Global Change and the Ecology of Cities,” Nancy Grimm et al. Science, Feb. 8, 2008 pp 756-760

“Upending the Traditional Farm,” Gretchen Vogel. Science, Feb. 8, 2008 pp 752-753

“Paint the Town White–and Green,” Arthur Rosenfeld, Joseph Romm, Hashem Akbari, Alan Lloyd. Technology Review, Feb. 1997

“Smaller Footprint: Vancouver’s Plan to Spread Upward,” Linda Baker. Sierra, July-Aug., 2007

“Unclogging Urban Arteries,” Elizabeth Quill. Science, Feb. 2008. pp 750-751

“Lights! Water! Motion!,” Viren Doshi, Gary Schulman, Daniel Gabalon. Strategy + Business, Spring 2007

“Random Samples: Going Under,”Science, Apr. 6, 2007. p 27

“Thronged, Creaky and Filthy.” Economist, May 3, 2007.

A formal version of this prediction appears online here, where it can be discussed and voted on.

Haseltine made the remark in a 2008 interview with GBN researchers about the future of biotech.

3.

Urban Promise

The city is all right. To live in one

Is to be civilized, stay up and read

Or sing and dance all night and see sunrise

By waiting up instead of getting up.

—Robert Frost, A Masque of Mercy

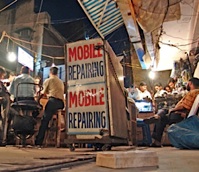

When the BBC sent a reporter and film crew to Kenya in 2007, they found a cellphone-summoned flash mob of squatters surrounding bulldozers that were about to force evictions. They found a farmer using what he calls his new middleman—his cellphone—to compare tomato prices in several remote towns. They found cattle ranchers checking with their far-flung herders by cell. A young woman in Nairobi said her cell was now her office: “It allows people to be able to own themselves,” she said. “It’s as big as fire, the wheel, and the railway.” Cellphone text messaging is spreading literacy. Cellphone directness works around government graft. Economic development and social change follow the cell towers wherever they go.

The poor of the developing world have turned cellphones into currency. Technology researcher Alex Pentland at MIT reports:

In some parts of Africa and south Asia, banking is done by moving around the money in cellphone accounts and people pay for vegetables and taxi rides by SMS [Short Message Service—texting].…

The great monetizer is prepaid SIM (Subscriber Identity Module) cards —a business worth $3 billion across Africa in 2007, run by local entrepreneurs. SIM cards are sold at vegetable stands and the like, along with “scratch cards” that reload the SIM with additional minutes. Some people carry just a card and borrow a phone when needed. Safaricom, in Kenya, has a service called M-Pesa that lets the cell work as an ATM; to send someone money, you text-message the appropriate code to them, and they get cash from a local M-Pesa agent. Cellphone minutes are traded by phone as a cash substitute. Credit card payments are made by cellphone. Remittances from relatives overseas come by cellphone. (Amounting to about $350 billion a year these days, remittances are expected to reach $1 trillion soon; in some developing countries, the remittance total is already higher than foreign aid and foreign investment combined.)

A South African company called Wizzit offers bankless banking via cellphone, with services I wish we had in California.…

An NGO in the Republic of the Congo provides smart phones “to local teachers, elders and business leaders so that they can report incidents of children being drafted as soldiers.” Some phones include games that teach languages. Nokia is producing cellphones that have seven address books, for multiple users.

Cellphones are demonstrating how continent-scale “incremental infrastructure” can be built, writes Harvard-based blogger Ethan Zuckerman. All an entrepreneur needs is one cell tower, which can be financed by selling handsets to local customers. As revenue comes in, another tower is built.…

The boundless resourcefulness of the poor is evident in slides shown at conferences by Jan Chipchase, Nokia’s field ethnologist of tech improvisation in the developing world. He has photos from Indian slums of whole streets of cellphone repair shops, where local talent has reverse-engineered every handset in the world and produced illustrated repair manuals in the local language. One of his slides shows a shabby doorway in a Uganda slum. Over the turquoise-painted door is a hand-lettered “077399721.” It’s not a street address, it’s a cellphone number. The world’s slums are the first urban environments to shape themselves around cellphones.

The bottom of the pyramid is no longer just an overlooked market, it is a creative engine for national economies. “From essentially zero,” writes Joel Garreau at the Washington Post, “we’ve passed a watershed of more than 3.3 billion active cellphones on a planet of some 6.6 billion humans in about 26 years. This is the fastest global diffusion of any technology in human history. … Cellphones are the first telecommunications technology in history to have more users in the developing world than in the West.” American travelers are often shocked to find that cellphone connectivity is better in developing countries than in the United States.

Technology historian Kevin Kelly draws an interesting conclusion from this:

A decade ago many folks who like to worry about the advance of technology were worried about the “digital divide.” This phrase signified the unfair gap between those who had computers and the internet and those who did not. The question was usually framed in these words: “What are you going to do about the digital divide?”

At the time my standard reply was, “Nothing. This is a case of the haves and have-laters.…

The oldest story in the world, the Epic of Gilgamesh, was set down in cuneiform four thousand years ago. It celebrated was has been called the first city in human history—the Sumerian capital, Uruk. Not coincidentally, Uruk was the first great center of writing. In the epic, a terrible flood wipes out every human and every creature except for those saved in an ark by the heroic Uta-napishtim. The Babylonian flood had a different cause than Noah’s flood in the Bible, which was written more than a thousand years later. David Damrosch writes in The Buried Book (2007):

The underlying problem was not human iniquity, as in the Bible, but the fact that the human race was multiplying uncontrollably, and people had begun making too much noise.…

It all reads like an early chapter in Steven LeBlanc’s chronicle of “constant battles” brought about by fecund humanity perpetually colliding with carrying capacity. Thomas Malthus told the same story in An Essay on the Principle of Population (1798); so did my teacher Paul Ehrlich, whose book The Population Bomb (1968) put overpopulation at the top of the Green agenda. His book begins: “The battle to feed all of humanity is over. In the 1970s and 1980s hundreds of millions of people will starve to death in spite of any crash programs embarked upon now.” It concludes with Ehrlich recommending “compulsory birth regulation,” including government-provided sterilants in water and staple foods.

_________

What environmentalists did with the population issue I can illustrate with a personal account. In 1969 Ehrlich’s book inspired me to organize a public piece of reality theater, a hunger show we called Liferaft Earth. Modeled on the civil rights sit-ins of the time, it was to be a “starve-in.” Well-fed Americans would starve for a week voluntarily, to draw attention to all those in the world starving involuntarily and the millions more who would soon do so because of overpopulation.…

Paul Ehrlich himself was involved in the next chapter. In 1972 the United Nations convened the first global forum on environmental issues in Stockholm.…

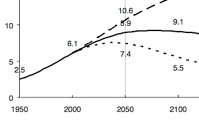

A population optimist, Wallace Kaufman, wrote in 1994: “Fortunately, population growth is likely to level off between 12 and 15 billion midway through the next century.” In the apocalyptic, highly influential 1972 book, Limits to Growth, the authors foresaw exponentially increasing population reaching a condition of “overshoot” of Earth’s carrying capacity, followed by a population crash.…

Development expert Paul Polak points out that the need for extra children among the rural poor is thoroughly rational:

A one-acre-farm family in Bangladesh needs three sons to get ahead—one to help with the farm, one to get a good enough education to land a government job capable of supporting the family from small bribes, and one to get a local job that pays enough to keep his brother, the one aiming for a government job, in school. But to end up with three sons means having eight babies, two of which are likely to die before the age of five, leaving three boys and three girls.

What happens in the cities is described by George Martine in the 2007 UN report Unleashing the Potential of Urban Growth: “In urban areas, new social aspirations, the empowerment of women, changes in gender relations, the improvement of social conditions, higher-quality reproductive health services and better access to them, all favour rapid fertility reduction.…”

How high a peak? The UN’s “median” projection in 2008 was that population would reach a little over 9 billion, but that figure is based on the assumption that birthrates in developed countries will start rising again for some reason. Because that seems unlikely, I think a more probable peak will be 8 billion, followed by a descent so rapid that many will consider it a crisis.

For every woman you know (or are) who has no children, some other woman has to have 4.2 just to keep the population even, and they don’t. Geneticist William Haseltine puts it harshly: “There’s a very odd phenomenon which seems to be a cultural invariant: once women gain economic independence, they do not reproduce our species.” In most cases, just the prospect of economic independence does the trick, and that’s what moving to cities provides.

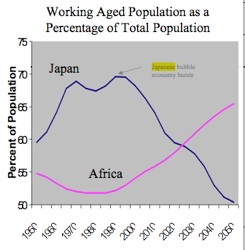

Because urbanization is currently taking place most rapidly in developing countries, the drop in birthrate is most rapid there, which means those nations are aging the most rapidly, though the effects won’t be felt for a while. In Mexico the birthrate dropped from 6.5 in the 1970s to about 2 in 2008, and it is still falling. By midcentury, Phillip Longman predicts, “Mexico will be a less youthful country than the United States.” Fertility rates are falling so fast in the Mideast and India, he says, that those regions are aging at three times the rate of the United States.…

How did Japan get itself into a seemingly permanent recession after the dazzling prosperity of the 1980s? Longman told a San Francisco audience:

Japan boomed through the end of the 1980s, so long as declining fertility was still increasing the relative size of its working-age population. … Japan’s long recession began just as continuously falling fertility rates at last caused its working-age population to begin shrinking in relative size.

Because Japan welcomes no immigrants, it is facing the world’s worst elder-care crisis. At Global Business Network, we predict that Japan’s standard solution to labor problems will be applied. Highly sophisticated, lovable robots and robotic environments will take care of Japan’s elderly, and then the technology will spread to the rest of the developed world.

The nation with the most alarming outlook is Russia. The birthrate is 1.14. The average Russian woman has seven abortions. One of the demographers at Global Business Network chiseled the nation’s epitaph in a 2008 report:

There is no historical precedent for a national population which is simultaneously aging and shrinking, as is occurring today in Russia.…

In Europe, birthrates have been declining steadily for four decades. How do you reverse that? Pope Benedict complained in 2006, “Children, our future, are perceived as a threat to the present.” Governments have tried everything to encourage more children. The Australian government has a three-child policy—“One for mum, one for dad, and one for the country”—and its birthrate remains at 1.8.…

“Poor countries with low and falling fertility rates are growing wealthier faster than rich modern countries,” wrote Ben Wattenberg in his 2004 book on depopulation, Fewer. “We live in a youthful world,” says a 2006 UN report. “Almost half of the global population is under the age of 24…. Fully 85 percent of the world’s working-age youth, those between the ages of 15 and 24, live in the developing world.”

Liberty ships, the torpedo fodder of World War II, were built on the Sausalito, California, waterfront at a peak rate of one a day in 1944. When the war was over, the former shipyard became a semioutlaw area, and riffraff moved in—floated in. Steadily, through the 1950s and 1960s, the tidelands filled with floating shacks, derelict boats, and habitable sculpture, occupied by artists, maritime artisans, and other people who had more nerve than money.

It was a community, Calthorpe decided, because it was walkable.

Building on that insight, Calthorpe became one of the founders of New Urbanism, along with Andrés Duany, Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk, and others. In 1985 he introduced the concept of walkability in “Cities Redefined,” an article in the Whole Earth Review. Since then, New Urbanism has become the dominant force in city planning, promoting high density, mixed use, walkability, mass transit, eclectic design, and regionalism. It drew one of its major ideas from a squatter community.

There are a lot more ideas where that one came from. For instance, shopping areas could be more like the lanes in squatter cities, with a dense interplay of retail and services—one-chair barbershops and three-seat bars interspersed with the clothes racks and fruit tables. “Allow the informal sector to take over downtown areas after 6 p.m.,” suggests Jaime Lerner, the renowned former mayor of Curitiba, Brazil. “That will inject life into the city.…”

People get around by foot, bicycle, rickshaw, or the universal shared taxi variously called a matatu (Kenya), dala-dala (Tanzania), tro-tro (Ghana), jeepney (Philippines), tuk-tuk (Thailand), tap-tap (Haiti), maxi-taxi (Romania), etc. (Not everything is efficient in the slums, though. In the Brazilian favelas where electricity is stolen and therefore free, Jan Chipchase from Nokia found that people leave their lights on all day.)

In most slums recycling is literally a way of life. The Dharavi slum in Mumbai has four thousand recycling units and thirty thousand ragpickers; six thousand tons of rubbish are sorted in the slum every day. In Vietnam and Mozambique, an article in the Economist reports, “Waves of gleaners sift the sweepings of Hanoi’s streets, just as children pick over the rubbish of Maputo’s main tip. Every city in Asia and Latin America has an industry based on gathering up old cardboard boxes.” There’s a whole book on the subject: The World’s Scavengers (2007), by Martin Medina. Lagos, Nigeria, widely considered the world’s most chaotic city, has an Environment Day on the last Saturday of every month. From seven to ten a.m. nobody drives, and the entire city, including the slums, tidies itself up.

_________

In his 1985 article that introduced the idea of walkability, Peter Calthorpe made a statement that still jars most people: “The city is the most environmentally benign form of human settlement. Each city-dweller consumes less land, less energy, less water, and produces less pollution than his counterpart in settlements of lower densities.” “Green Manhattan” was the inflammatory title of a 2004 New Yorker article by David Owen. “By the most significant measures,” he wrote,

New York is the greenest community in the United States, and one of the greenest cities in the world. …

The idea of measuring environmental impact in notional acres was introduced by Mathis Wackernagel and William Rees in the 1996 book Our Ecological Footprint, as a way to estimate the resource efficiency of large systems like cities and as a way to condemn suburban sprawl. The concept has been tremendously useful in shaming cities into better environmental behavior, but comparable studies have yet to be made of rural populations, whose environmental impact per person is much higher than city dwellers. Nor has footprint analysis been applied to urban squatters, who will certainly score as the Greenest of all.

Urban density allows half of humanity to live on 2.8 percent of the land. Soon that will be 80 percent of humanity on 3 percent of the land. Consider just the infrastructure efficiencies. According to a 2006 UN report, “The concentration of population and enterprises in urban areas greatly reduces the unit cost of piped water, sewers, drains, roads, electricity, garbage collection, transport, health care, and schools.” In the developed part of the world, cities are Green mainly because they reduce energy use, but in the developing world, the primary Greenness of cities lies in their ability to draw people in and take the pressure off rural natural systems.

The Last Forest (2007), a book by Mark London and Brian Kelly on the realities of the Amazon rain forest, suggests that the nationally subsidized city of Manaus in northern Brazil “answers the question ‘How do you stop deforestation?’ Give people decent jobs.…

Mayors travel routinely, cruising for ideas in the cities deemed the world’s Greenest—Reykjavik, Iceland; Portland, Oregon; Curitiba, Brazil; Malmö, Sweden; Vancouver, Canada; Copenhagen, Denmark; London, England; San Francisco, California; Bahi de Caráquez, Ecuador; Sydney, Australia; Barcelona, Spain; Bogotá, Colombia; Bangkok, Thailand; Kampala, Uganda; and Austin, Texas. Urban ecotourism is a growth industry.

To manage the ecology of cities, we first have to understand it. A 2008 article in Science framed the necessary new discipline in meaty language I find delicious:

Evolving conceptual frameworks for urban ecology view cities as heterogeneous, dynamic landscapes and as complex, adaptive, socioecological systems, in which the delivery of ecosystem services links society and ecosystems at multiple scales. …

One idea that could be transferred from squatter cities is urban farming. Another article in Science enthused:

In a high-tech answer to the “local food” movement, some experts want to transport the whole farm—shoots, roots, and all—to the city. They predict that future cities could grow most of their food inside city limits, in ultraefficient greenhouses.…

According to a 1997 study from the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, “If the 100 largest cities in the world replaced their dark roofs with white shingles and their asphalt-based roads with concrete or other light-colored material, it could offset 44 metric gigatons (billion tons) of greenhouse gases.” Call the program “Alabaster Cities,” and you can invoke “America the Beautiful” in support. (It’s the best line in the song: “O beautiful for patriot dream/ That sees beyond the years/ Thine alabaster cities gleam/ Undimmed by human tears.”)

Some environmentalists already are proponents of urban compactness. Sierra Club’s magazine reports that in Vancouver, “Mayor Sam Sullivan’s EcoDensity program includes zoning changes to allow ‘secondary suites,’ or in-law apartments; triplexes; and narrow streets with houses that abut property lines.” Peter Calthorpe’s “walkability” has become a real estate selling point, with walkable neighborhoods able to charge premium prices. A proven way to encourage walking and use of public transit is with a “congestion tax” on cars in the downtown streets. In 2002 London followed the lead of Singapore and Hong Kong and adopted the practice of charging cars ₤8 a day to drive in the central city.…

Infrastructure makes cities possible, and it has to be rebuilt every few decades. According to a report in 2007 by the infrastructure consultants Booz Allen Hamilton, “Over the next 25 years, modernizing and expanding the water, electricity, and transportation systems of the cities of the world will require approximately $40 trillion.” What would infrastructure totally rethought in Green terms look like? China is currently building 170 new mass transit systems.…

The night side of Earth, these decades, displays a dazzling lacework of light on the continents, with incandescent nodes at the metropolitan areas and a bright tracery of transportation corridors between them. That web of light is the sign to any visitor that they are approaching not just a living planet, but a civilized planet.…

A nice service scoring the walkability of various neighborhoods in US cities is here.

The definitive graph proving the reality of the “demographic transition” that Barry Commoner espoused is here.

A blogger named Yorkshire Ranter says of M-Pesa: “As this is actually in my own field of specialisation; MPESA actually started off as a Vodafone Group CSR project part funded by the UK Department for International Development. Safaricom is a VF partner network, though they don't own it.

“Safaricom rolled it out, and then indeed, the street found its own uses etc. But it started off with a bunch of besuited OSS-BSS systems consultants, Vodafone executives, and international-aid civil servants. It just looks favela chic — inside it's British and Swedish SQL monkeys all the way down:-)”